Growing up on the east coast of England, photographer Mandy Barker loved to stroll the local beaches and collect driftwood and shells. These days, she strolls beaches around the world collecting plastic. She hauls micro-plastics and large pieces back to her studio where she produces striking photographs, drawing viewers in to the reality of what they’re looking at—an abundance of harmful waste. Collaborating with scientists (even joining them on expeditions), Barker hopes to raise awareness about plastic pollution in our oceans and to inspire others. She is a recipient of the 2018 National Geographic Society Grant for Research and Exploration and her work has appeared in various international publications including The Guardian, Time Magazine, Vogue, and National Geographic. Her gorgeous first book Beyond Drifting: Imperfectly Known Animals was named on the Ten Best Photography Books of 2017 by Smithsonian. Last year, Barker collaborated with Stanford University to create a virtual reality experience called Ripple: the unintended life of plastics in the sea in which viewers interact with the ocean’s plastics via a 360° headset. —Jane Ratcliffe

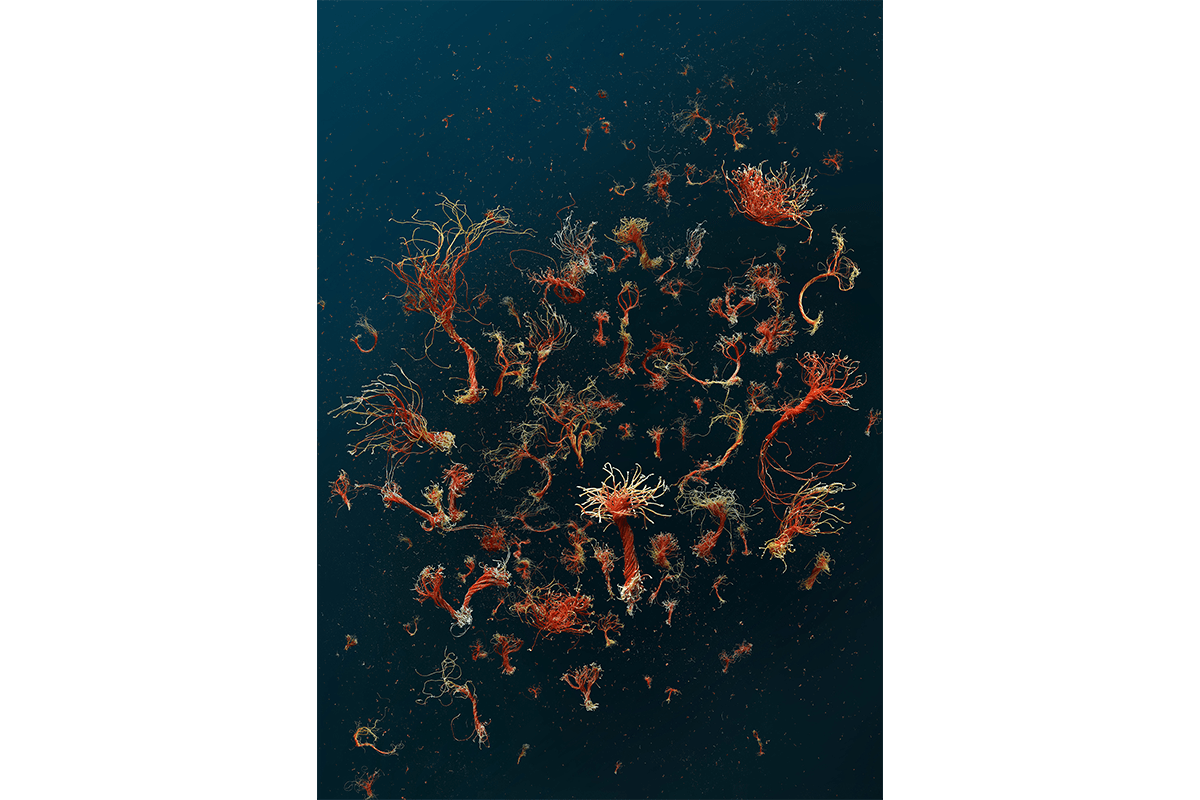

SOUP: Refused, Photograph © Mandy Barker

What led you to photography and then specifically focusing on marine plastic debris?

Personal experience. I grew up on the East coast of England, and during my childhood I enjoyed being by the sea and collecting natural objects such as driftwood and shells. Increasingly over the years these natural objects have been taken over by man-made waste, especially plastic. I began to notice household appliances such as fridge freezers, computers and TV casings, child’s car seats and more washed up on the beach, and began to wonder how they got there. I felt this was an environmental concern that others should know about, and this is what stimulated my work—to spread awareness of this experience to a wider audience.

SHELF-LIFE: Barcode – 50P 300015, Photograph © Mandy Barker

What do you wish to convey with your photographs?

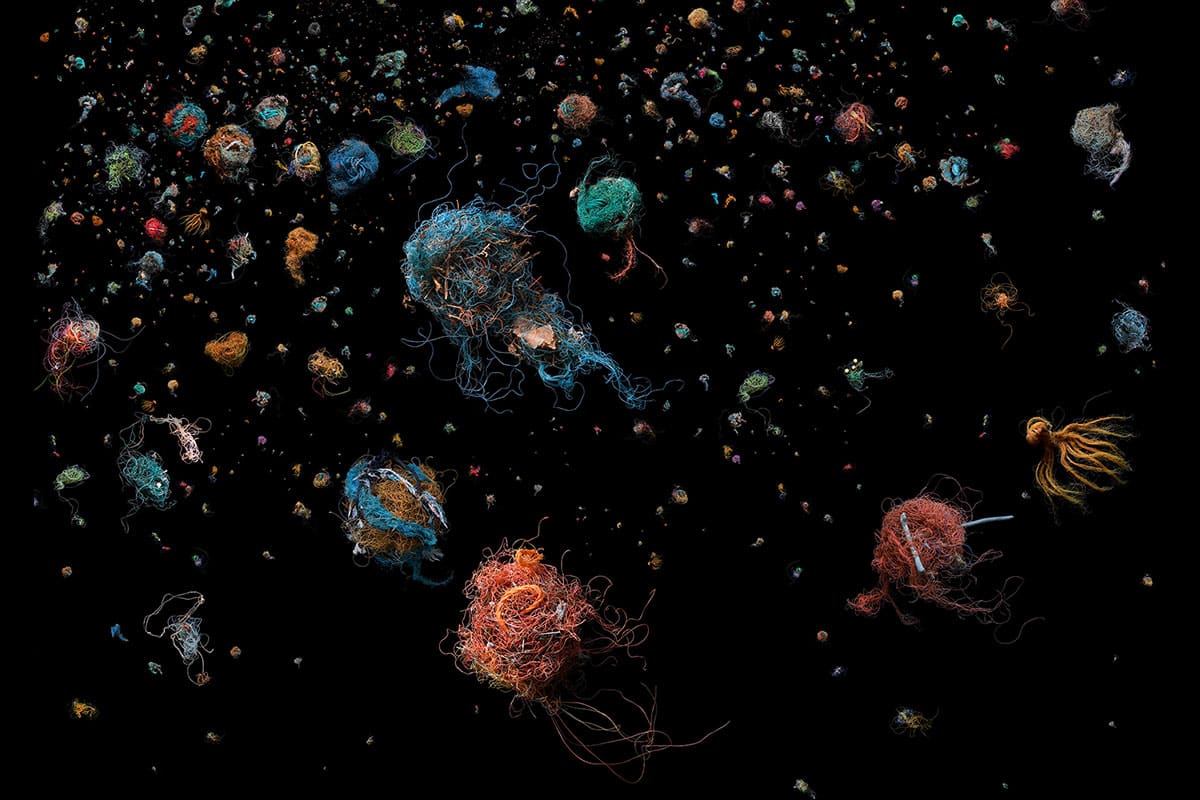

I aim to engage the viewer through aesthetically pleasing images, drawing them in, and then shocking them with the captions and information of what they are actually looking at. I hope this engagement will increase awareness about the issue of plastic pollution through the type of objects that are found in the world’s oceans, from protected global environments to the stomachs of marine creatures, and ultimately ourselves. My main aim is to encourage people to take responsibility for their own plastic use on a daily basis, to stimulate debate, and to change legislation regarding the production and manufacturing of unnecessary plastic, and in doing so, help to inspire change.

LUNASEA: Grid Of Objects, Photograph © Mandy Barker

You’ve been on several expeditions, once joining Greenpeace, to collect plastic debris. Can you tell us about them?

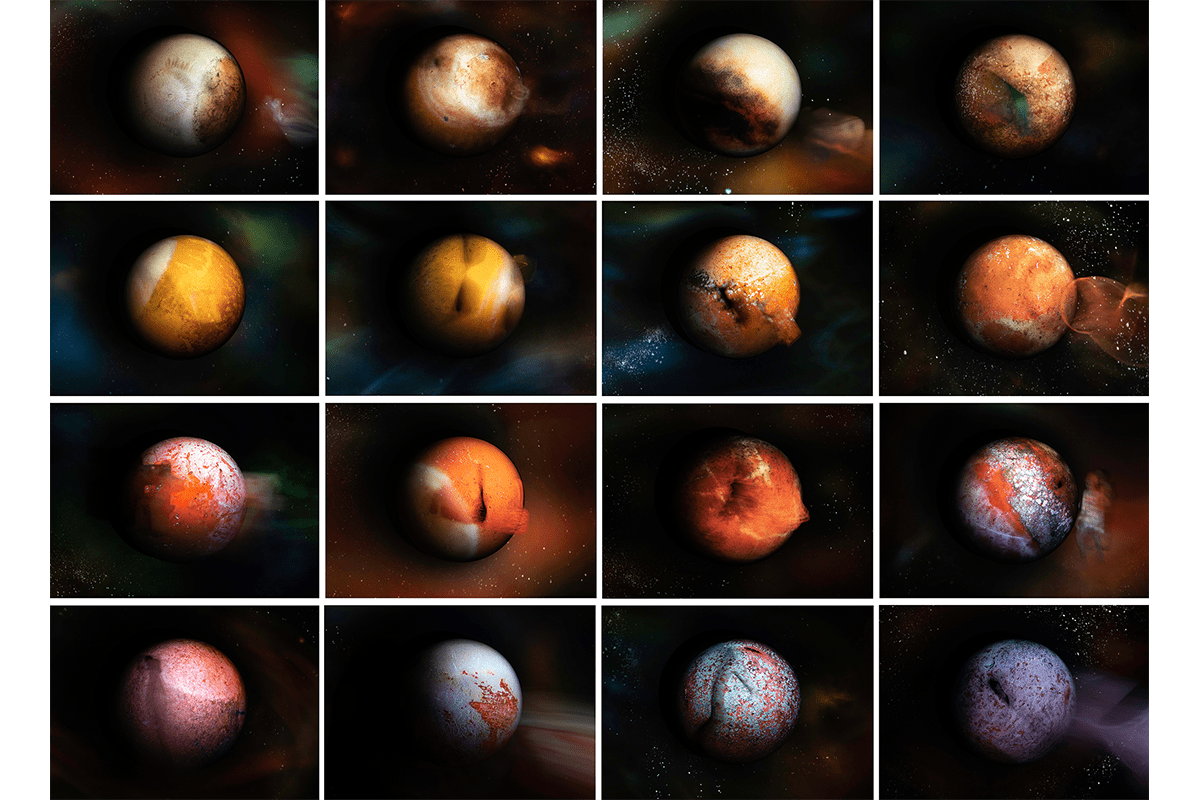

I have taken part in several expeditions that have crossed world oceans, working alongside scientists to see their work first-hand and to create work that can go on to support and enhance their research—almost giving science a visual voice. In 2012, I sailed with a team of 12 across the North Pacific Ocean through the tsunami debris field for a month on a yacht, which resulted in the series SHOAL. Last year, I took part in an expedition to Henderson Island, which is a remote uninhabited island isolated in the middle of the South Pacific Ocean. This UNESCO world Heritage site is more than 5,000km from the nearest major landmass and has been named as the most plastic polluted beach on the planet. During the expedition I photographed most of the 6 tons of plastic on the islands shores and have created different projects to try and engage different audiences with more than 45 recognized brands from over 25 different countries, and with objects including a skating boot, syringes, inkjet cartridges, a McDonald’s Happy Meal toy, and a toilet seat.

PENALTY – The World, Photograph © Mandy Barker

Do you personally collect all of the plastic debris used in your work?

I recover most of the plastic myself, but people do help and I am often getting plastic items posted to me from all over the world with people asking me to include them in my images. However, I created the series PENALTY, specifically to get other people involved in the collection. Via a social media call out, I asked the public from all over the world to send me footballs (soccer balls) washed up on their local beaches and to post them to me to photograph. In the end I received 769 balls and created 4 images that showed the different collections from the world, Europe, United Kingdom, and a collection from a single person. The project received a really good response from all areas. It was broadcast live on CNN News Connect the World along with dialogue and images showing the concerns of marine pollution and single-use plastic. The project itself connected the public with the issue from some of the places the footballs were found. For example, one of the balls travelled across the North Pacific from Japan after the tsunami and was found on the West Coast of the United States. The project also inspired environmental education in schools with pupils recovering plastic waste and balls lost on waste ground to create their own images inspired by the PENALTY series.

Hong Kong Soup:1826 – Transform, Photograph © Mandy Barker

Do you shoot all your photographs in a studio? How do you create the illusion that all the items are floating?

Most of my work is shot in a studio, but on expeditions, it is not possible to bring back the plastic, and it may be required for scientific research so I often have to photograph on location. During the expedition across the North Pacific, I photographed all plastic recovered on board the yacht, which was very difficult due to rough conditions. On Henderson Island I photographed most of the plastic in a cave on East Beach.

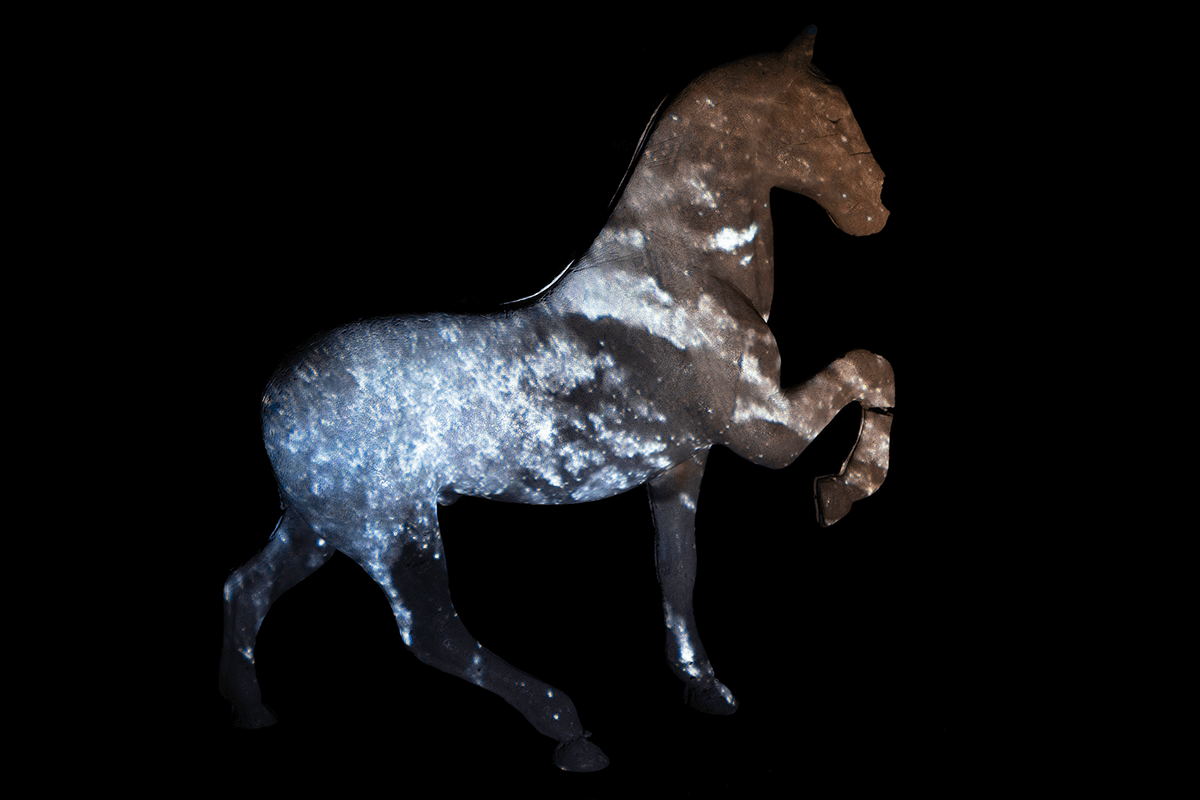

I place varying sizes of the plastic—from micro-plastic particles to larger foreground objects—on a black background. Combined with an exposure of a few seconds, and with light from one direction source, this creates a feeling of infinity and the effect of suspension. For the Beyond Drifting: Imperfectly Known Animals series I used a broken 35mm film camera, and for one of my recent expeditions to Henderson Island I used a camera made from the actual marine plastic debris itself. Each project is a conscious decision to reflect a different aspect about the issue of plastic debris and my work is evolving all the time, trying to engage in new and different ways.

SHELF-LIFE: Barcode – 490250 5085680, Photograph © Mandy Barker

What was the 3D project you collaborated on with Stanford University?

I collaborated with Stanford University to launch a virtual reality experience of my work, Ripple: the unintended life of plastics in the sea. I worked with Stanford’s Communication Programme in Journalism with several of my images to represent how ubiquitous plastic has now become part of our world, creating an experience freely available to everyone across all platforms, from a 360º headset to a mobile phone.

Do you have any favorite organizations or people spearheading the fight against marine plastic debris?

There are significant individuals and organizations around the world that are doing fantastic work in the fight against plastic pollution in terms of getting petitions signed, campaigning and getting acts passed. It is hard to select but as for individuals, the amazing work of Ella and Caitlin McEwan, aged 8 and 10, in the UK who started a petition to ban plastic toys being given away with Burger King and McDonald’s Happy Meals, shows just how powerful and engaged the younger generation can be. Being successful in changing toys that have been given away for the past 40 years, is an incredible achievement from school children, and goes to show we all have the power to make change for the better.

LUNASEA Object No.46 – Horse, Photograph © Mandy Barker

What would you like to see governments around the world do to tackle plastic pollution?

I would like to see government legislation that requires manufacturers to take responsibility for collecting and recycling their materials or products after use; to have the return deposit scheme implemented so that the consumer will be encouraged to take their plastic bottle or other container back to where they bought it so that it doesn’t end up in the environment; to have single-use packaging replaced with an ethical alternative; and to stop the shipment of plastic waste to developing countries that don’t have the ability to manage it.

LUNASEA Grid of Moons (fishing buoys recovered from Henderson Island), Photograph © Mandy Barker

What gives you hope?

That the above will happen. People like Ella and Caitlin McEwan. And the comments book I leave in my exhibitions. If photography has the power to move people emotionally, encourage people to act or at the very least, make them take notice, then this must surely be a vital element to lead to change. If I didn’t believe my work did any of these things then I wouldn’t be motivated to continue.

SOUP: Bird’s Nest, Photograph © Mandy Barker

What are you currently working on?

My next project is the result of a residency I did last year on Lord Howe Island in Australia, concerning sea birds called shearwaters that live on the island. When the chicks come out of their burrow, they are sadly being fed plastic by their parents that mistake it for food when they forage out at sea. This is the first time I have worked alongside scientists where marine plastic is directly affecting a species. It’s an emotional experience and I hope to get that across in the work.