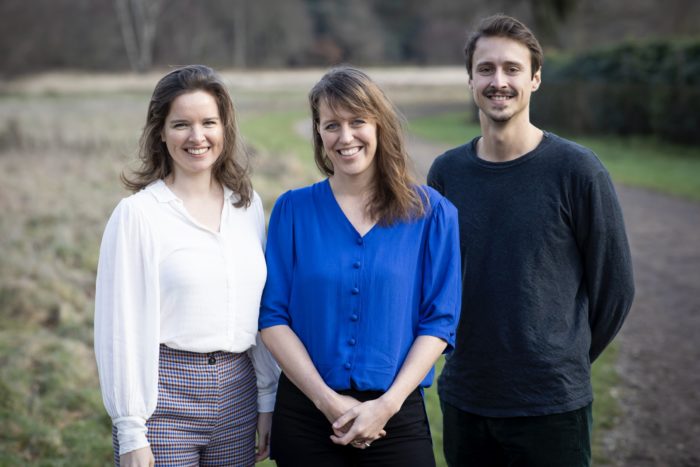

As an avid sailor, Francis Zoet has spent a lot of her time on the water. After continuously coming across plastic pollution, she became motivated to do something about it and knew that rivers are a major source of plastic waste in our oceans. That’s when Francis and her co-founders (Anne Marieke Eveleens and Philip Ehrhorn) came up with The Great Bubble Barrier. They pump compressed air through a perforated tube that runs diagonally across the bottom of a river, which creates a curtain of bubbles with an upward current directing plastic to the surface. Once it’s at the surface, the plastic—as small as one millimeter and as large as one meter—is pushed toward the catchment system. From there, it’s sorted and analyzed in collaboration with the Plastic Soup Foundation. The first long-term Bubble Barrier was installed in Amsterdam, Netherlands in 2019, and currently captures 15,536 pieces of inorganic waste every month. They also have Bubble Barriers in Katwijk, Netherlands, Vila do Conde, Portugal, and Harlingen, Netherlands with many other projects in the pipeline for Europe and abroad.

As an avid sailor, you’ve spent a lot of time out on the water. When did you first notice the severity of plastic pollution?

When you are out on the water frequently, you encounter plastic pollution everywhere, all the time. During sailing trips, with two of our other co-founders, we found ourselves annoyed and alarmed by the amount of plastic in waterways. A big issue is how fragmented the plastic becomes when left in the water. We started wondering if there were any technologies to clean rivers and remove the plastic, without obstructing daily river activities. Because it didn’t exist yet, we decided to develop a solution ourselves: A Bubble Barrier.

How does your technology work?

We create a bubble curtain by pumping compressed air through a perforated tube on the bottom of the waterway. The bubble curtain creates an upward current which directs plastic to the surface. By placing the Bubble Barrier diagonally across the river, the natural flow of the water will push the plastic waste to the side and into the catchment system. The catchment system is designed to work in harmony with the bubble curtain to collect and retain plastics. Following collection, it will be removed for processing and reuse.

Why is the tube placed on a diagonal in the river?

By placing the Bubble Barrier diagonally across the river, the natural flow of the water will push the plastic waste to the side and into the catchment system. The bubbles act as a guide for the plastic, steering it to a preferred collection point.

If the bubble curtain is strong enough to direct plastic and waste, how does it avoid harming wildlife? Are fish ever stuck in the catchment system?

Fish can pass through the bubble curtain and under our catchment system. Together with renowned ecologists and fish experts, we performed various research on fish behaviour around our bubble curtain which shows that fish migration is not hindered.

Our Bubble Barriers are designed to stop as much plastic as possible with the least amount of air possible. It is a single curtain, in contrast to some fish deflection screens of e.g. six curtains in a row. There are no additional stimuli, like light and sound. Therefore, the set-up differs quite strongly from the bubble curtains used for fish deflection and we can say with certainty that our Bubble Barrier doesn’t block fish.

Nevertheless, we find it important to keep researching fish behaviour around our bubble curtains. Our latest research focused on smaller fish around the Bubble Barrier Amsterdam. This research showed smaller fish passing through the Bubble Barrier and underneath the catchment system. Due to the complexity of fish behaviour, we will always continue our collaboration with ecologists.

Where and how is the plastic processed?

Plastic caught by our Bubble Barriers (Amsterdam and Katwijk) is collected by the Water Authority who in turn send it to a recycling centre. Waste management can differ significantly per country and location, so each Bubble Barrier is tailored to the local waste management infrastructure.

In Amsterdam, part of the catch was collected monthly for a research study led by the Plastic Soup Foundation together with Waternet to underpin the exact amount, type, brand, and origin of the plastics.

We are also currently exploring with partners on how to recycle our collected plastics to turn them into items that improve people’s lives and contribute to a circular economy. However, as a tech start-up, we focus our efforts on the efficacy and deployment of the Bubble Barrier technology and its catchment system. Other great innovative start-ups are focusing exclusively on sorting, identification, and recycling.

How does The Great Bubble Barrier hold up in environments like tidal rivers where the direction of flow is continuously changing?

Our Bubble Barrier in Vila do Conde, Portugal, was the first time we placed our technology in a tidal river with positive results. Changing flow directions does not hinder the plastic capture. Before implementation, we perform extensive feasibility research which maps out the location characteristics (e.g. flow speed and direction). When a river’s flow direction changes, emptying the system can be planned during times with the preferred flow. Bubble Barrier Amsterdam has changing flow directions with great results: we capture 15,536 pieces of dried, inorganic waste per month in this location.

What are the most common types of plastic found in the catchment system?

After sorting Bubble Barrier Amsterdam’s catch into the twelve main OSPAR categories, we observed that the most common material found (over 71%) was plastic. When dividing the total plastic, we found that the largest category is plastic foam (such as styrofoam), followed by soft plastic (such as food wrappers), and then hard plastic (such as PET bottles).

In a pilot conducted in Berlin, our Bubble Barrier system proved that it could catch particles as small as 1 millimetre up to 1 metre. We often witness this in the sorting activities we conduct in collaboration with the Plastic Soup Foundation, where we have found a staggering number of styrofoam particles.

We know that microplastics (particles smaller than 5 mm) are directly derived from macro plastics, therefore it is crucial to collect those items before they reach the seas where it will be impossible to retrieve them as currently there is no technology to collect nonvisible microplastic (smaller than 1 mm).

How many Bubble Barriers are currently set up and where are they located?

The Great Bubble Barrier has implemented four long-term Bubble Barriers to date. The first long-term Bubble Barrier was implemented in Amsterdam, Netherlands in 2019. Since then, we have implemented Bubble Barriers in Katwijk, Netherlands (2021), Vila do Conde, Portugal (2023) and Harlingen, Netherlands (2024).

We have many projects in the pipeline and hope to grow and scale our solution in the coming years across Europe, and internationally.