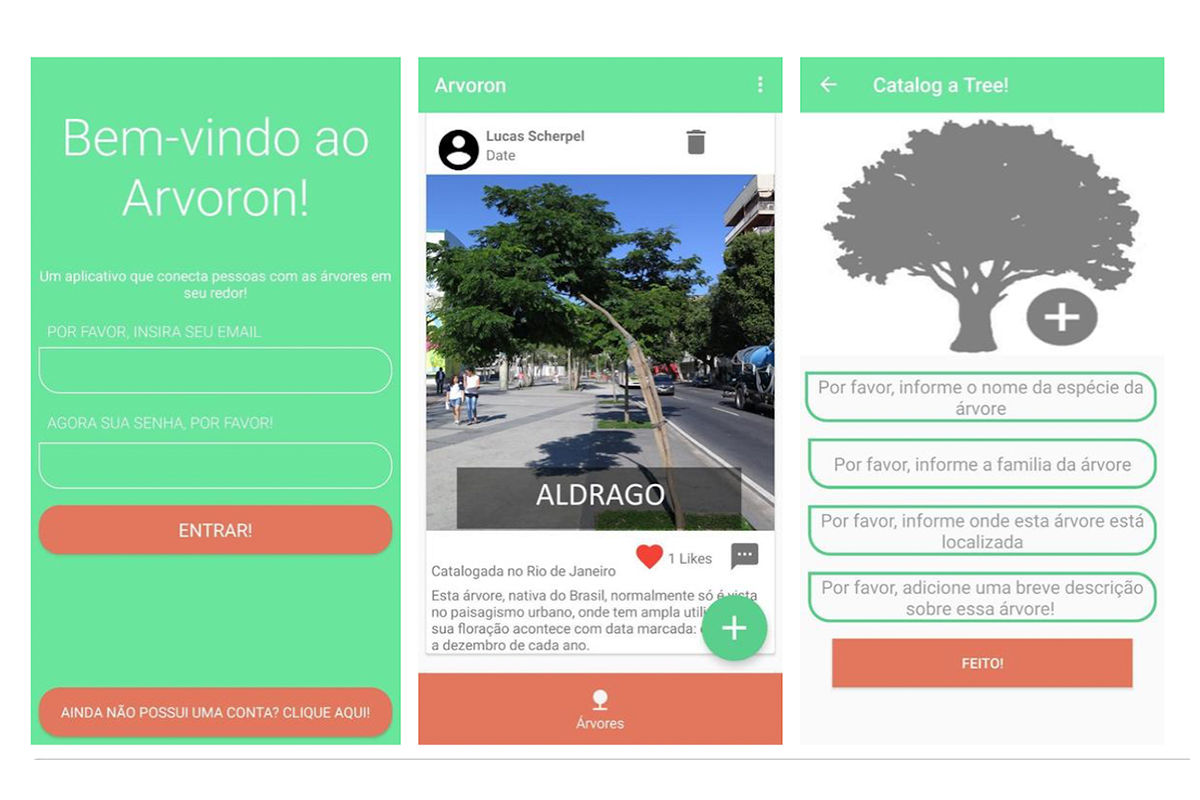

Growing up in Rio de Janeiro, teenager Lucas Scherpel  was dismayed to see the way his fellow citizens treated trees. Rather than being in awe of their magnificence and showing them respect, the community chopped them down, fearing they would fall on their cars or homes. Scherpel recognized the profound benefits of the trees: they filter air pollutants and prevent urban heat islands—areas that become dangerously hot due to human activity. And they also provide a sense of calm and tranquility amidst the bustle of city life. Scherpel spent one year researching urban forestry. Then, as a skilled programmer, he channeled his passion into developing an app, Arvoron, for Androids that educates people on the importance of the trees. Not only does it identify the tree, it provides a social network for likeminded urban environmentalists. The app was so successful that in 2017, it won Brazil’s Prudential Spirit of Community Award. This year, he is a Global Team Leader for the We Are Family Foundation.

was dismayed to see the way his fellow citizens treated trees. Rather than being in awe of their magnificence and showing them respect, the community chopped them down, fearing they would fall on their cars or homes. Scherpel recognized the profound benefits of the trees: they filter air pollutants and prevent urban heat islands—areas that become dangerously hot due to human activity. And they also provide a sense of calm and tranquility amidst the bustle of city life. Scherpel spent one year researching urban forestry. Then, as a skilled programmer, he channeled his passion into developing an app, Arvoron, for Androids that educates people on the importance of the trees. Not only does it identify the tree, it provides a social network for likeminded urban environmentalists. The app was so successful that in 2017, it won Brazil’s Prudential Spirit of Community Award. This year, he is a Global Team Leader for the We Are Family Foundation.

What does the urban landscape around Rio de Janeiro look like today?

Nowadays, it’s undeniable that most of the world’s population lives in urban centers. And Brazil, especially Rio de Janeiro, does not differ from that global trend. On the last statistics made, Brazil’s tax of urbanization was 85 percent, and that number only tends to grow. That urbanization process results in the creation of extremely modified areas, with different characteristics that existed before. Because of that, urban forestry seems to be a necessary element in this new landscape—not only in an aesthetic way, but to prevent ecological issues that normally happen in urban centers.

Growing up in the large city of Rio de Janeiro, I noticed that the surrounding urban landscape was often ignored and mistreated. Community members viewed trees only as potential hazards, fearing they could fall on cars or buildings, and therefore, encouraged cutting them down. That’s the scenario I’ve been working to change since 2015.

Do you think your app is making a difference in Rio and elsewhere?

My app has brought environmental awareness to citizens around Rio, but it has also started this new movement for creating apps and other technologies focused on the environment. For example, after my appearance in Veja Rio magazine, one of the most famous and historical botanic gardens in Brazil launched its own environmental app. Arvoron also called the attention of environmental organizations who started to rethink how to catalog trees around cities, using Arvoron as an option to replace the use of paper.

Your app provides a social network for people who are also concerned about trees amidst cityscapes. What sort of community is forming there? Have any social activist undertakings grown out of it?

Our community ranges from nature lovers and environmental engineers to the CEO of the urban forestry organization of Rio. Arvoron supports all positive environmental actions—activities involving planting trees; park revitalizations; social garbage collection; and manifestations focused on Brazil’s environmental issues.

How long did it take you to develop the app?

It took me two months. Nonetheless, in 2015, I spent one year doing research on urban forestry before getting into the app. During this period, I had one of the most difficult challenges so far: throwing myself in the streets to study more than one hundred trees that existed around my community in order to have some data available on my app for people to see.

What goes into developing this sort of app? Do you have to take pictures of all the trees in Brazil?

I used to study every species I found in my community and take pictures of them to add on the app. But, as the project grew, it became impossible for me to handle this by myself. The capital of Rio alone has around 800,000 to 1,000,000 trees.

Now, I offer the app as a tool for environmental organizations across Brazil and they put the images and information about the trees in the app. It’s helpful for them since Arvoron works as a reliable database to store the data, and it’s helpful for the population who have access to free and valuable information on trees in their surroundings. Information about the trees includes their scientific name, family, a description, images, and places nearby that you can find them.

Do you have plans to expand Arvoron beyond Brazil?

Actually, we have had people from six different countries download the app! But I don’t think they took the best experience out of it since the project focused on Brazil at that time. One of my goals is to engage environmental organizations around the world to fill Arvoron’s database with their local trees’ information so people from other countries, just like before, can download the app and gain more environmental awareness from it.

Might the app one day include flowers and even weeds?

Arvoron is a tool for organizations to share valuable information about trees in urban centers. If any organization sees the inclusion of flower, weeds or anything related to the environment as necessary information for citizens to acknowledge, then I’m open to it.

Why is it so important to save the trees?

Trees mean life. Caring about the trees is caring about your life. They provide oxygen, combat climate change, save water, provide food, cool down cities and much more.

We often take trees for granted since it’s an ordinary thing in our daily lives. That’s why one of my catchphrases is, “Since trees don’t have a mouth to speak for themselves, I’m willing to be their voice!”

President Bolsonaro is not supportive of the environment and has already taken steps to undermine the protections in place. What are your thoughts on this?

Unfortunately, it’s not just Bolsonaro. The new minister of the environment in Brazil, nominated by the president himself, portrays a regression on turning this nation into a more sustainable and environmentally-aware country. Brazil has the biggest tropical deforestation percentage in the world and actions executed by the government (like denying climate change), abolish essential forest reserves. Cutting investments on environmental areas will not shift the situation. However, I’m still confident that impactful projects and new environmental activists will bloom and grow from this dark time and become the resistance from the government’s unfortunate decisions.

What are you working on now?

Besides Arvoron, I work on a non-profit organization called Construindo o Futuro, focused on supporting and bringing SDGs projects to communities and schools around Brazil. I also developed a mobile app called Vençapp which teaches users how to become more sustainable via daily habit-changing challenges. This July, I was in Tanzania representing Brazil at the Young Global Pioneers program. And I’m starting to work with AI and Machine Learning so by the end of the year, I want to launch a startup using these technologies focused on enhancing people’s lives.

How did it feel to win such a prestigious award?

Winning Brazil’s Prudential Spirit of Community Awards in 2017 was definitely the turning point in my life and on my project as well. After that, I started getting featured in magazines and TV shows, and went to a leadership bootcamp in Colombia. I also represented Brazil at the 2019 Three Dot Dash Global Teen Leaders program after five years without any Brazilian getting accepted to it. The award was the opening gate for many more grateful moments in my life.