Self-proclaimed “sciartist:” Part Brown-educated environmental scientist and part RISD-educated artist. Her vibrant yet fragile depictions of our oceans’ threatened ecosystem have been causing quite a stir. Origin Magazine pronounced her one of 2015’s top 100 “Ocean Heroes,” and the International SeaKeepers Society named her Artist of the Year. It’s easy to see why. Her colorful and often sprawling pieces are a delight, yet their message is urgent: We must reverse climate change now or all of this will be gone. Courtney hopes by bringing the staggering damage that’s happening in the oceans above the surface and into galleries (such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), people will begin to deepen their understanding of just what’s at stake—and take action.

Your work is so intimate and precise. How do you go about sculpting each element?

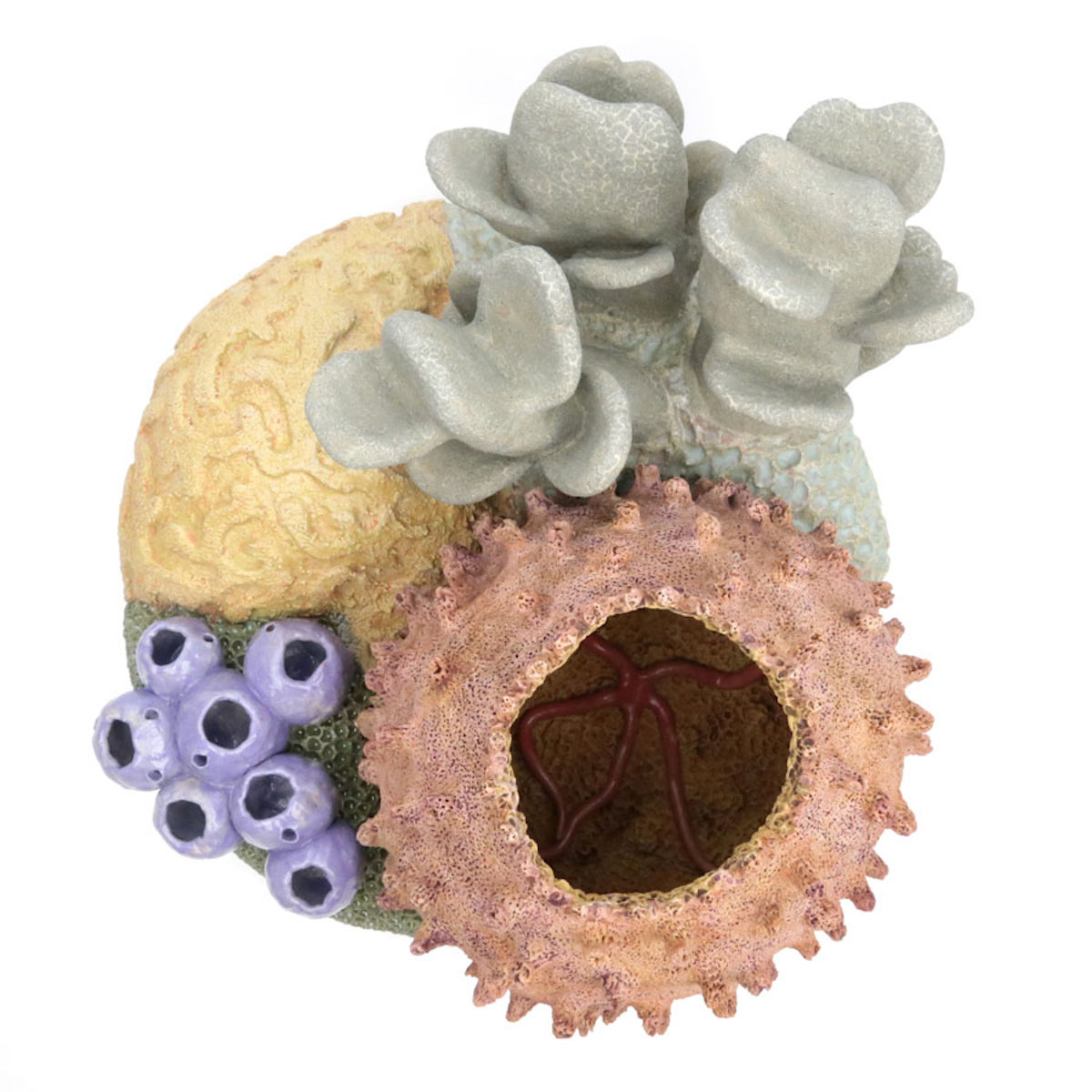

My work is definitely a labor of love! I hand-build everything very methodically in my “Inland Sea Studio” in Denver, CO and texture the work using simple tools like chopsticks and paintbrushes. I sculpt delicate components like anemone tentacles and protruding coral polyps from porcelain, and roll out coils of gritty stoneware sculpture clay and pinch them together layer by layer to build the more massive pieces, which are all hollow. Once a piece is finished, I let it dry for a few days (or weeks depending on size) before firing it along with others in one of my two electric kilns. For sustainability reasons I always try to load my kilns as full as possible to cut down on energy consumption. Once a piece is fired it’s ready to be glazed and fired a second time.

Once each element is finished, how do you gather them all into one sculpture?

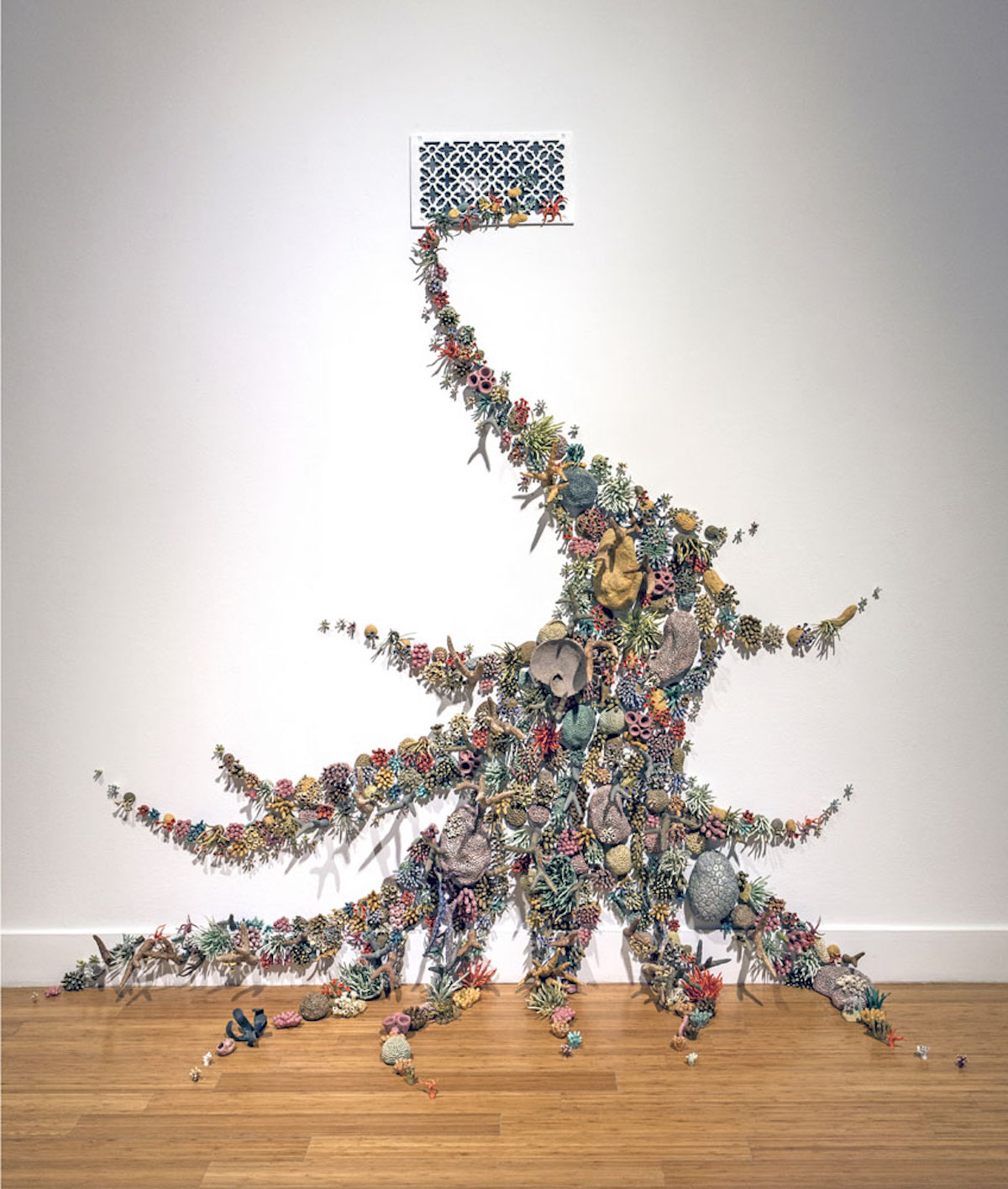

For my larger installations (like in my Our Changing Seas series) many components install like puzzle pieces and must be built to fit together. For works like Our Changing Seas III I build each part in relation to one another on a grid marked out on the floor of my studio. Doing so allows me to keep track of where the mounting hardware needs to go on the back of each piece, ensuring that the art handlers installing the work know where each piece goes. For more fluid installations comprised of many tiny pieces like my latest work, Aqueduct, it’s more important for there to be a good variety of pieces of different sizes, forms and colors that I can figure out how to install together on-site in the exhibition space. That latter type of installation allows me to improvise and adapt the installation to be more site-specific, and I can add more pieces to it over time. Aqueduct, for example, will look different wherever I install it next and it will likely grow in size.

How long does it take you to complete an installation?

That all depends on the size and complexity of the work. I sculpt very quickly, but the multi-step process of creating, firing and glazing ceramics inherently requires time and patience. Drying work before the first firing is a delicate process, and if rushed can lead to cracking, or worse, explosions! To avoid any accidents I always have multiple pieces in progress at the same time and wait to fire everything until it’s completely dry.

I worked full-time (and overtime) to create Our Changing Seas III for its debut exhibition at the Tang Museum in 2014. From when I started designing it to when every piece of the installation was complete took about six months. That felt really fast! I worked more slowly over the course of four months to create Aqueduct to debut at my current solo show, Sea Change, at the Virginia Museum of Contemporary Art.

via Courtney Mattison

Do you first make sketches? Or are you working from photographs? Or do your pieces evolve organically?

I do like to start with sketches when designing installations and large sculptural works. When creating smaller pieces, like for my Hope Spots series, however, I prefer to allow the works to evolve more organically as I build while referencing photographs. I always bring a camera when I go scuba diving and have collected hundreds of images that I reference for much of my work.

How was your work received at RISD? Was it unusual to be combining your sculptural studies with your environmental studies at Brown?

When I applied to masters programs in environmental studies, Brown was at the top of my list in a major part because of its connection to RISD and the relative ease with which it allows students to transfer credits between the two institutions. I feel so fortunate to have had that experience of doing nearly half of my coursework at RISD in a truly interdisciplinary blend of conservation biology, policy, social science and fine art. Some of my RISD classmates probably didn’t know what to think of me, or perhaps had trouble thinking of me as a true artist. It was kind of funny (and a little frustrating at times) because I felt like I was perceived as more of a scientist at RISD and more of an artist at Brown, where I was studying environmental science. Having that dual life for those formative two years forced me to declare what I had already known since my interdisciplinary studies at Skidmore College: I am a sciartist.

Art and science are inherently interconnected in my work, and there’s no reason for me to be just an artist or just a scientist, especially if the results are greater than the sum of their parts.

Aside from my personal journey in graduate school, studying ceramics at RISD marked a really important period in my development as an artist, because that’s where I was able to take part in lots of critiques and spend an entire summer testing glazes in the glaze chemistry lab. My RISD instructors and critique-mates encouraged me to “go big” with my work—to create sculptural installations that could alter entire exhibition spaces and overwhelm viewers with my message. I’m glad I took them seriously!

via Courtney Mattison

Are you optimistic or pessimistic about the recovery of our oceans?

I am optimistic, although I know the data surrounding ocean health are dire. The combination of human-caused climate change, ocean acidification, overfishing, land-based sources of pollution and other major pressures are wreaking havoc on marine life around the globe, making vital ecosystems like coral reefs sick and threatening their survival. But, at least we understand and can develop solutions to these threats; it’s just a matter of inspiring the world to care enough to act urgently to mitigate them. To quote oceanographer Dr. Sylvia Earle, “ignorance is the biggest problem of all for the ocean.” Many people simply don’t know or care that the ocean is in trouble, or that humanity’s welfare relies on a healthy blue planet.

I am hopeful that cultural platforms like contemporary fine art, filmmaking and photography can quickly raise awareness by translating the science of climate change and other threats into calls to action that individuals find personally compelling.

Many who view my work have never experienced a truly pristine coral reef in the wild and may never get that chance to do so. By bringing the beauty and peril of coral reefs and other marine ecosystems above the surface and into view, perhaps my work will inspire people to care more wholeheartedly about protecting them.

via Courtney Mattison

What do you want people to take from your work?

I want viewers to feel the way I do when I slowly hover over a coral reef while scuba diving, discovering tiny details in every crevice and feeling as though they’re among precious—and very delicate—life forms. I want people to feel inspired and curious, and then I want them to understand how tragic it would be to lose these ecosystems and to feel empowered to help.

News about the environment is bleak. It seems like every day we are inundated with more stories about how humans are destroying the planet. All of this doom and gloom doesn’t inspire people to care or change their ways. It makes us feel helpless and guilty, so we ignore the problem and change the channel, believing that someone else will invent a way to fix it or it will go away on its own. This apathy is especially true for ocean-related issues that are largely out of sight, out of mind.

If art can lure us in, if it can spark a sense of curiosity and make us feel a positive connection to the exquisite and fragile forms of coral reef invertebrates and other critters that we don’t think of on a daily basis, we will develop personal ties to them.

Connections like this are what will drive us to vote for leaders and policies that value environmental preservation, make lifestyle and budgetary choices that prioritize sustainability, and use our skills—whatever they may be—to save the planet.

Art has a unique power to influence how we understand our lives and our planet, and can make us connect emotionally to concepts or environments that we would otherwise ignore.

We protect what we care about, and we care about what we know and understand. Art can bring the plight of coral reefs, for example, above the surface and into view, making us appreciate their fragile beauty and empathize with the threats they face in ways that drive us to change our behavior.

How has your work with Mission Blue shaped your art?

I have admired Mission Blue founder and National Geographic Society Explorer-in-Residence Dr. Sylvia Earle since my first marine biology class in high school. Dr. Earle is a role model for so many marine researchers and explorers (and women!), including myself, so it’s a dream come true to work with her foundation to advocate for ocean conservation by sharing her story and spreading awareness about marine protected areas—which Dr. Earle calls “Hope Spots”—as effective conservation tools.

The concept of Hope Spots—Earth’s most vital marine ecosystems worth protecting through a global network of marine protected areas—speaks to me as it does thousands of people around the world. Hope Spots are the inspiration for one of my current series of the same name comprised of circular wall-mounted ceramic sculptural vignettes. Each one represents a different marine region identified as a Hope Spot by Mission Blue. The series is leading me to branch out from coral reef ecosystems to creating works that represent all kinds of different marine habitats, from shallow seagrass meadows to deep sea trenches and hydrothermal vents that researchers have barely explored.

via Courtney Mattison

Do you have a sense of whether your work is having an impact?

I’m thrilled whenever I receive a letter or email from someone who finds my work inspiring. I hear from many students, and teachers of younger students, about ways in which my work has motivated them to help protect the ocean. Hundreds of students are visiting the Virginia Museum of Contemporary Art where my current solo show is up through April 17, which really excites me because the museum has a gallery adjacent to my exhibition called ARTlab that empowers visitors to help by creating “oyster castles” to restore Chesapeake Bay’s oyster reefs and learn about ocean conservation organizations they can support in the region.

View more of Courtney’s work.