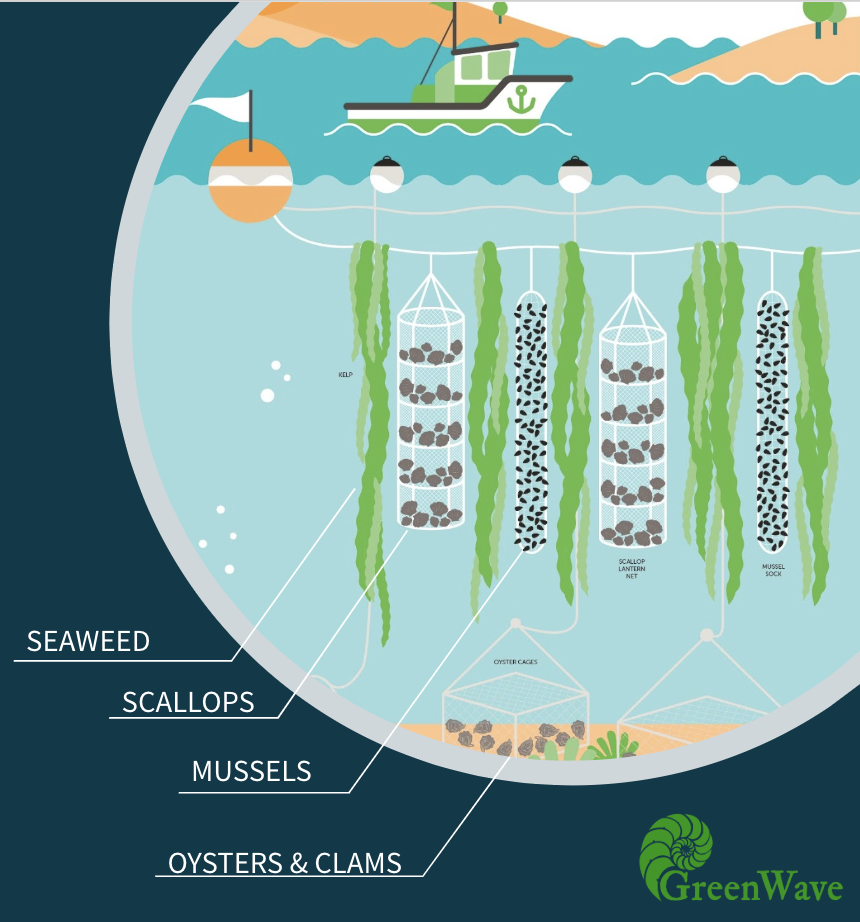

Born  and raised in a small fishing village in Newfoundland, Canada, Bren Smith left school at 14 years old and headed out to sea, fishing for tuna, lobster, cod and crab. In the early ’90s, the cod stocks crashed and thousands of fishermen were thrown out of work. He wound up on the Long Island Sound and became an oysterman until taking hard hits from Hurricanes Irene and Sandy. “Suddenly I found myself on the front lines of a climate crisis that had arrived one hundred years earlier than expected,” he says. After exploring and experimenting, Bren founded GreenWave, a regenerative ocean farming model, with Emily Stengel. Imagine an underwater garden running from the surface to the seafloor—home to an abundance of kelp and other seaweed varieties, scallops, mussels, clams and oysters. These ocean crops require zero input, can restore ocean ecosystems, capture blue carbon and create millions of jobs.

and raised in a small fishing village in Newfoundland, Canada, Bren Smith left school at 14 years old and headed out to sea, fishing for tuna, lobster, cod and crab. In the early ’90s, the cod stocks crashed and thousands of fishermen were thrown out of work. He wound up on the Long Island Sound and became an oysterman until taking hard hits from Hurricanes Irene and Sandy. “Suddenly I found myself on the front lines of a climate crisis that had arrived one hundred years earlier than expected,” he says. After exploring and experimenting, Bren founded GreenWave, a regenerative ocean farming model, with Emily Stengel. Imagine an underwater garden running from the surface to the seafloor—home to an abundance of kelp and other seaweed varieties, scallops, mussels, clams and oysters. These ocean crops require zero input, can restore ocean ecosystems, capture blue carbon and create millions of jobs.

—Charlotte DeFazio

How did you get started? What led to founding GreenWave?

I was born and raised in a little fishing village in Newfoundland, Canada. I left school at age 14 and headed out to sea. I fished the Georges Banks and the Grand Banks for tuna and lobster, then headed to the Bering Sea, where I fished cod and crab. But in the early 1990s, the cod stocks crashed back home: thousands of fishermen thrown out of work, boats beached, canneries shuttered. In a search for sustainability, I ended up on Long Island Sound and remade myself as an oysterman. Then in two successive years, Hurricanes Irene and Sandy thrashed the East Coast, destroying my crops and washing my gear out to sea.

Suddenly I found myself on the front lines of a climate crisis that had arrived one hundred years earlier than expected. I began to reimagine my occupation and farm—experimenting and exploring new designs and new species. In 2014, I co-founded GreenWave with Emily Stengel to replicate the regenerative ocean farming model, and scale its ecological and economic benefits. We want to create a thriving blue-green economy—built and led by ocean farmers—that ensures we all make a living on a living planet. We train regenerative ocean farmers and at the same time, build viable market opportunities to ensure their long-term success. Our goal is to train 10,000 ocean farmers in the next 10 years.

Tell us about your regenerative ocean farming model.

GreenWave’s polyculture farming system grows a mix of seaweeds and shellfish that require zero inputs—no freshwater, no fertilizers, no feed. They simply grow by soaking up nutrients, making it, hands down, the most sustainable form of farming on the planet. Since our farms sit vertically below the surface, they produce high yields with a small footprint. With a low barrier to entry, anyone with 20 acres, a boat, and $20-50K can start their own farm.

The model is easy to replicate. It’s just an underwater scaffolding that’s affordable and easy to build. The simple design and low cost mean these farms can be replicated quickly. It has the potential to revitalize coastal economies by utilizing existing infrastructure and latent capacity in shuttered fishing communities, diversify existing shellfish businesses, and provide a stream of supplemental income for fishermen. Beyond food, diverse markets are opening up for regenerative ocean crops including fertilizer, animal feed, bioplastics and more. In addition to commercial farming, regenerative ocean farming can be deployed for reforestation, to restore ocean ecosystems and capture blue carbon.

Which species are grown and how much does that vary depending on location?

There’s one hard and fast rule for regenerative ocean farming: grow only zero-input species that won’t swim away and don’t need to be fed. Picture the farm as a vertical underwater garden: hurricane-proof anchors on the edges connected by horizontal ropes floating six feet below the surface. From these lines, kelp and other kinds of seaweed grow vertically downward, next to scallops in hanging nets that look like Japanese lanterns and mussels held in suspension in mesh socks. On the seafloor below sit oysters in cages, and then clams buried in the mud bottom.

On our farm, we’ve experimented with a few different kinds of seaweed, but sugar kelp has emerged as the most productive, delicious and viable native species in southern New England. Sugar kelp (Saccharina latissima) is a prolific and versatile cold-water seagreen (or rather, brown macroalgae) that grows in northern waters across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The regenerative ocean farming model can be adapted for use in other regions with native seaweed and shellfish species.

Doesn’t seaweed harvesting date back to the early 1900s? What were they using it for and why did the industry drop off?

Seaweed harvesting dates back millennia, popping up as a mainstay of the diets of coastal communities and trading partners on every continent. But seaweed is incredibly versatile. As far back as the eighteenth century, coastal economies in Europe and the United States harvested wild kelp to turn into a potassium-rich ash for pottery, glass, soap, and textiles. Irish moss, which is 40 percent carrageenan, was turned into a thickener or stabilizer for processed foods, ranging from chocolate milk to beer. Between 1950 and 1970, Canada became the world’s leading supplier of carrageenan.

In the early 20th century, Asia saw seaweed as a food source, while the U.S. focused on seaweed as an industrial ingredient for fertilizers and chemical weapons. During World War I, California’s wild kelp beds were wiped out, deforested for conversion into acetone and potash for munitions. At its height, the industry employed 1,500 workers on the San Diego docks.

With World War II looming, the U.S. military became increasingly concerned that demand would outstrip supply, both from within the United States and from foreign sources in Japan. This triggered interest in whether seaweed farming could fill the anticipated gap. The Department of Energy invested in research, but focused on producing seaweed on a mass industrial scale with farm designs that were too complicated, capital intensive and expensive to be viable.

That history underscores how critical it is that we build a sustainable seaweed supply and diverse market opportunities to keep regenerative ocean farmers in business. Part of GreenWave’s work is to build strong connections between farmers and buyers across growing sectors like food, agriculture (fertilizer and compost) and bioplastics, as well as emerging opportunities like blue carbon and nitrogen offsets and data harvesting.

What are the main concerns that people have about regenerative ocean farming?

The concerns that come up most often tend to center around aesthetic impact and privatization of the ocean. Countless aquaculture projects suffer quick deaths when communities mobilize in opposition. Regenerative ocean farms have a small footprint while producing a huge amount of food. The model is a win for farmers and a win for local communities. It’s low-impact and designed to tread lightly on the ocean commons. And because it’s mostly underwater, from shore there’s minimal aesthetic impact. Best of all, locals can continue to boat, fish, and swim; the goal is to protect, not privatize, the ocean.

The other question that we often get is whether regenerative ocean farms have a negative impact on endangered species. In more than a decade of farming along the coast, we’ve never had a marine mammal or sea turtle entangled. Our farms are designed to make this a minimal risk.

How many jobs could be created with this model? What has been the general stance on this from the commercial fishing community?

According to the World Bank, farming seaweed in less than 5% of U.S. waters (.1% of the world’s oceans) could create 50 million jobs in direct on-farm employment alone. Using a standard seafood industry secondary employment multiplier of 2:1 suggests 100 million jobs could be created overall, with additional economic opportunities created through processing, value added product production, transportation and marketing.

When I first started farming seaweed, I was getting laughed off the docks. What self-respecting fisherman would want to grow sea vegetables? But over time, many have come around to the idea. They see their catches declining, chasing fewer and fewer fish further out to sea, and they realize it’s time to shift. We’ve had an 11th generation fisherman go through the GreenWave training program. We also have requests to start farms in every coastal state in North America and over 100 countries around the world.

Is this a lucrative model for communities most at risk for hurricanes and massive storm damage?

The regenerative ocean farming model can be a lifeline for the revival of working waterfronts. First, the infrastructure is easy and inexpensive to set up. For fishermen and shellfish farmers, adding kelp cultivation to their business strategy helps to manage risk through crop and market diversification, extend their growing season, and increase revenue. New England has seen rapid expansion of the number of people interested in and actively growing kelp with approximately 100 nearshore small-scale kelp farms securing permits in coastal waters from New York to Maine since 2010, and interest from more than 1,000 people seeking to launch kelp farms or add kelp cultivation to their existing business.

A 20-acre farm growing shellfish and kelp can conservatively produce 130,000 lbs. of kelp and 200,000 lbs. of shellfish, with the capacity to net more than $100,000 on an annual basis. Fishermen see benefits from diversification, too. In Maine, lobstermen who have recently added kelp cultivation to their business report adding $20,000-$57,000 to their annual revenue at harvest time. In addition to all of these direct financial benefits, the model fosters healthy marine ecosystems that can support stocks of other fish species.

How easy is it to set up a local farm? Are certain areas much more difficult to obtain leasing and permitting?

The farm structure itself is easy to set up. Depending on your experience level, a whole farm can be installed in three days. Leasing and permitting, on the other hand, vary wildly depending on a variety of factors. If you are a shellfish farmer, well-acquainted with aquaculture permitting processes and gear types, it may only take a few months to modify your permit and incorporate kelp into your operation. If you are starting from scratch, are unfamiliar with ocean farming, and just want to grow seaweed, it could take 4-18 months to secure a site and permit.

And it really depends on where you want to farm. For instance, Maine has a longstanding commercial seaweed industry, and supportive pathways to permitting. In Connecticut, we had to work with the state legislature in 2012 to create a pathway to permit my farm. In California, the regulatory landscape is very different because the state is so protective of its pristine coastlines. There, we’re seeing tremendous interest in regenerative ocean farming for commercial and restoration purposes, and are working with a coalition of people in the field to demonstrate the ecological and economic benefits of the model and to develop reasonable pathways to get farms in the water. A core part of GreenWave’s work is to support farmers through these complex processes.

What is at stake in the upcoming U.S. election for the future of our oceans?

I was told climate change would be a slow lobster boil, but it’s here and now. The ocean is a place where we can build real climate solutions. No matter which way the wind blows in the upcoming election, we need serious reform in three specific policy areas: ocean habitat restoration, community based fisheries, and restorative ocean farming. With the support of better policies, we can shift the ocean from a resource in crisis into a powerful tool for mitigating climate change, transforming our food system, and ensuring that coastal communities have viable economic opportunities.

What are coastal Indigenous communities currently facing?

Coastal Indigenous communities are particularly vulnerable to the effects of the climate crisis, and are facing land loss due to rising seas and the decline of marine species. This is happening all over the globe. We’re currently in conversation with community leaders in the U.S., Canada, and New Zealand to identify ways to use the regenerative ocean farming model to support local ecosystems and economies. For instance, we’re working with the Native Conservancy, the Alaska Conservation Foundation, and other community partners in Southcentral Alaska to adopt the model to bring back wild kelp beds and herring stocks. Historically, both species have been critical sources of income and food security, as well as an important part of the region’s cultural heritage.

Are there any plans to expand outside of North America?

While GreenWave’s primary focus over the next 5 years will be to grow the regenerative ocean farming in North America, we’ve had tremendous interest from people around the world—more than 6,000 prospective farmers have reached out to us for help. We’re taking a cautious approach to global work, and are dipping our toes in the water through targeted partnerships with local organizations. To meet the growing demand in North America and beyond, we’re in the process of building out a digital resource platform, which will house tools and information to help farmers from seed to sale.