Dyeing textiles can be a dirty business. The World Bank estimates that 17-20% of industrial water pollution is from conventional petroleum-based fabric dyes and treatments. There are rivers in Asia that flow with the season’s on-trend color, and some waterways in Africa are as alkaline as bleach. Liz Spencer, known as The Dogwood Dyer, offers an alternative approach with her natural dyes that remind us of the importance of slowing down and appreciating quality over quantity. She transforms fabric with concoctions made from bark, leaves, roots, seed pods, nut husks, shells, and even veggie skins destined for compost. While studying in London for her Master’s in Sustainable Fashion, Spencer decided to try her hand at gardening. Since then, she’s been creating natural dye gardens wherever she goes from Brooklyn to California. And what she can’t grow, she forages. —Jane Ratcliffe

How did you first learn about natural dyes?

I discovered natural dyes by saying yes to an opportunity to fundraise, plan and build a dye garden with community members while studying sustainable fashion at the London College of Fashion. At first it was a fun activity and project that I thought would help me connect with the community and get outside, away from my computer and my knitting machine where I had been spending most of my time while pursuing my masters. It quickly became something I couldn’t keep from doing! For me, gardening and growing my own color has been an indispensable part of natural dyeing.

You use three different dyeing techniques: immersion, shibori, and painting. Can you tell us a bit about each one?

These three techniques are some of my favorites that I have included in my natural dye kit available on my website, but there are even more ways to create color with plants such as printing (block printing, eco printing, and screen printing to name a few), that become available to artists after learning the basics of dye science and art.

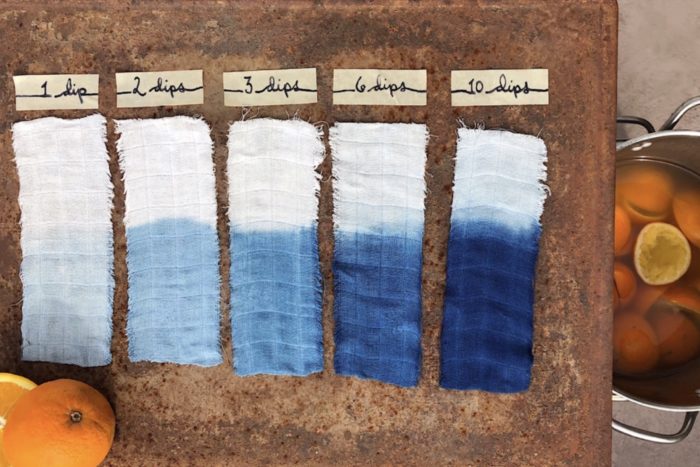

Immersion dyeing involves pretreating the whole textile for best absorption of dye then extracting the color from plants and introducing the fibers to the dye bath for an even swath of color (one of the most deceivingly simple yet challenging feats for the natural dyer).

Shibori is a Japanese take on “resist” dyeing that creates a surface design on the fabric while employing immersion dyeing. The resisted area of the fabric (whether it be protected by folding and pressing (called ‘Itajime’), stitching or binding with strong thread or rubber bands) is kept white or undyed while the rest of the fabric is dyed in the immersion bath. Shibori is particularly apt with Indigo dye because of the nature of the distinctly different process of dyeing with Indigo. Other ways of creating resist of fabric include using a thick liquid that dries on the cloth such as rice paste, cassava, soy paste, batik wax, etc.

Painting with natural dyes has recently become one of my favorite techniques because it can be used on many substrates such as paper or wood—not just textiles. I like to save my immersion dye baths after I have finished a dyeing session and concentrate them down to a powder that can be made into watercolor paints so that no precious natural dyes go to waste.

What do you love most about working with plants?

I love the constant education I must seek out while working with plants for dye. Natural dyeing has opened up so many doors to peripheral worlds of study for me such as chemistry, color theory, history and ethnobotany to name a few.

Do you practice any type of ceremony before or during dye extraction?

With three young children under my care, I am often fitting dye practice in here and there throughout the day so ceremony is not usually possible, but I will say that natural dyeing and growing my own color has attuned me to my plant surroundings and seasonal shifts. Each session in my studio may not always afford me a beautiful finished piece of textile, but at the end of the day, there is always a dye pot to give a last stir, fabric to hang, or glass jar to lid after filling with seed or flowers. Little tasks throughout the week or season really add up over time, especially at summer’s end!

How do things like weather, soil or time of day effect the extraction process?

Indigo pigment extraction, for example, can really flex or be variant depending on temperature and sun exposure. A pigment extraction from home grown indigo can take as little as 12 hours and can take as long as 4 days depending on the ambient temperature. Soil quality and type is huge for my garden depending on the harvest needs. If I am growing indigo, I’ll fertilize very differently than where I’m growing plants like hollyhock or cosmos because with indigo I’m after as much leaf weight as possible (where the dye lies) and with many other plants I grow, I’m seeking as much bloom as possible—so the soil will need very different nutrient content.

You also practiced fiber farming. What did that entail?

I did fiber farming with my partner years ago in what we call a ‘hobby’ farm, learning as we went. At one point we had over ten sheep, two alpacas and two llamas, plus dozens of other farm animals like chickens, goats and pigs. The work was hard and around the clock at times, but I’m grateful for the experience now having gained a much larger appreciation for organic, ethical food and fiber. I still have bags of fleece from our sheep and alpacas that I will process and spin and knit by hand I’m sure! The few garments I was able to create from shearing the animals ourselves to cleaning, carding, spinning and knitting the fibers all by hand are very treasured.

In addition to growing plants, you forage. What kind of plants are you looking for?

I currently live in Southern California where some of my favorite local natural dyes include oak, eucalyptus and cochineal (actually a parasitic insect that grows wild on prickly pear cactus here). I only pick small amounts or make use of what the city is pruning from trees already. My garden makes plenty of plant matter that keep my dye pots busy, but there’s nothing like trying a new plant in my local environment for the first time.

Does natural dye fabric require special care?

For the most part, natural dyes are not as resistant to light and physical abrasion with washing as synthetic dyes, but many natural dyes are very stable and can last years and years if the fabric is first cleaned really well (scoured) and pre-treated with the right natural fixatives (there are many plant and natural metal combinations that work). Picking the right plant for dye and pre-treating (called ‘mordanting’ in natural dyeing) are key to best results. With this in mind, it’s important to also care for naturally dyed textiles with consideration—washing with cold water and detergent that is free of enzymes and at a neutral pH is important for good colorfastness.

Is there a particular plant dye you most love to work with?

Very hard to choose but if I had to say it would be indigo! It acts so differently than all other plant dyes, and for the most part, because of its chemistry, it really is in a class of its own. There is so much to learn when working with this dye. Indigo can come from many different botanically unrelated plants too, originating from all parts of the globe and employed by so many different cultures, making it even more mysterious and globally resonant. I feel as if I will never learn all there is to know about indigo blue. And it’s hard not to love a plant that can make a color of the sky and oceans.

How can we turn our compost into dye?

There are many plants and plant parts that can become dye such as tree trimmings (all orchard fruiting trees like cherry, apple, etc.), municipal or city landscaping waste such as eucalyptus and oak trimmings, food waste such as avocado pits and onion skins, and even agricultural waste and byproducts (pomegranate skins, black walnut hulls and tobacco have dye potential). I teach about making dye from waste in my online workshops, and there’s nothing like giving it a try and experimenting with your own green waste to see about color potential.

As a mother of three, what do you hope to pass onto your children about caring for the planet?

I would love for my work to inspire my children to see beauty in all living things and to stop, notice, observe and connect with their natural surroundings regularly. This will hopefully in turn inspire them to be active stewards of resilient natural systems where their interactions are beneficial, not harmful. They already know full well that a hike with me might take longer than usual, but they’ll likely come away discovering something new.