Tired of the amount of plastic piling  up around the planet as well as the treatment of farm animals, Eben Bayer, CEO and co-founder of Ecovative Design, began growing mycelium. Rather than being reliant on petroleum, these products use local feedstock from crop waste such as seed husks and woody biomass (which means the material can be grown anywhere and is 100% compostable). Mycelium is the root structure of mushrooms and, as it turns out, is a wondrous and versatile product. Ecovative has currently developed three platforms around it: Atlast Food Co (Ecovative’s spin-off company) in which the structure of mycelium serves as “edible scaffolding” for meat replacement. Their Atlast Bacon is expected to launch within the next year; MycoFlex in which, as the name suggests, flexible mycelium provides sustainable alternatives to everything from plastics to leather; and MycoComposite in which the mycelium serves as biodegradable packing material. And there are more applications in the works. If ever there’s a remake of The Graduate, Mr. McGuire’s one word for Ben will no longer be “plastics,” rather “mushrooms.” As this profile comes out, I am at Post Ranch in Big Sur for a mycelium retreat with Louie Schwartzberg, director/producer of Fantastic Fungi, and Paul Stamets, a pioneer of the mycoverse and its many amazing attributes to heal ourselves and the planet. I am so looking forward to the launch of Ecovative and Atlast’s latest innovations. —Jane Ratcliffe

up around the planet as well as the treatment of farm animals, Eben Bayer, CEO and co-founder of Ecovative Design, began growing mycelium. Rather than being reliant on petroleum, these products use local feedstock from crop waste such as seed husks and woody biomass (which means the material can be grown anywhere and is 100% compostable). Mycelium is the root structure of mushrooms and, as it turns out, is a wondrous and versatile product. Ecovative has currently developed three platforms around it: Atlast Food Co (Ecovative’s spin-off company) in which the structure of mycelium serves as “edible scaffolding” for meat replacement. Their Atlast Bacon is expected to launch within the next year; MycoFlex in which, as the name suggests, flexible mycelium provides sustainable alternatives to everything from plastics to leather; and MycoComposite in which the mycelium serves as biodegradable packing material. And there are more applications in the works. If ever there’s a remake of The Graduate, Mr. McGuire’s one word for Ben will no longer be “plastics,” rather “mushrooms.” As this profile comes out, I am at Post Ranch in Big Sur for a mycelium retreat with Louie Schwartzberg, director/producer of Fantastic Fungi, and Paul Stamets, a pioneer of the mycoverse and its many amazing attributes to heal ourselves and the planet. I am so looking forward to the launch of Ecovative and Atlast’s latest innovations. —Jane Ratcliffe

What drew you to this work? Tell us a bit about Ecovative’s inception.

I grew up farming in Central Vermont—pigs, chickens, forest products, maple syrup, big garden living off-grid and off the land. I was really into technology—jet engines, computers, nanobots, and wanted to get off the farm. I went to Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute to study mechanical engineering, and within a year of arriving, had three life-changing realizations:

- I really missed living in concert with nature. I had no idea how unsustainable the rest of the world was.

- Nature (trees, plants, animals, bacteria, yeast), not machines, is the greatest technology in the world.

- I wanted to devote my time on spaceship earth to using technology (untapped natural technology) to help humans live happier, healthier lives in harmony with our planet.

This brought me to reflection on the different living systems I had worked with and ultimately to an under-recognized sub category of fungi: mycelium, the root structure of mushrooms.

We’ve used it as food (mushrooms) for hundreds, thousands of years. Then I started asking: What if we looked at this organism, not as only a food source, but as a material? This was a pretty crazy idea, both in terms of the approach and problem we were addressing. Back in 2007, when Ecovative was founded, climate change and environmentalism were something only the counterculture was talking about. I was fortunate to have a mentor and first investor, Burt Swersey, who pushed me to take the leap and start Ecovative. Now the world is waking up. It’s predicted that by 2030 there will be more plastic in the ocean than fish. If our Mushroom® Packaging ends up in the ocean, it’s fish food. That is the common good we’re going after. It’s not just about carbon dioxide; it’s about toxicity reduction for the planet.

We see the same opportunity with the leather-like textile we developed as well as our work in creating the world’s first whole-cut, plant-based meats—starting with Atlast Bacon. Each of these product lines touch a major source of human emission and worldwide impact.

It seems that there are new mycelium products appearing on the market almost daily. What makes yours different?

In 2006 there was no “mycelium product” or “mycelium materials.” The idea didn’t exist. We created this entire new branch of science back then. We’re thrilled to see so many products entering the market as well as universities starting research programs around mycelium. Most of the mycelium composites and mycelium materials you read about are actually made under license from Ecovative (we have over 40 patents in 31 countries on the fundamental art of mycelium materials), but we make it very easy for folks to start a business with this technology. You can even buy a $13 GIY Kit from us to get started in your kitchen.

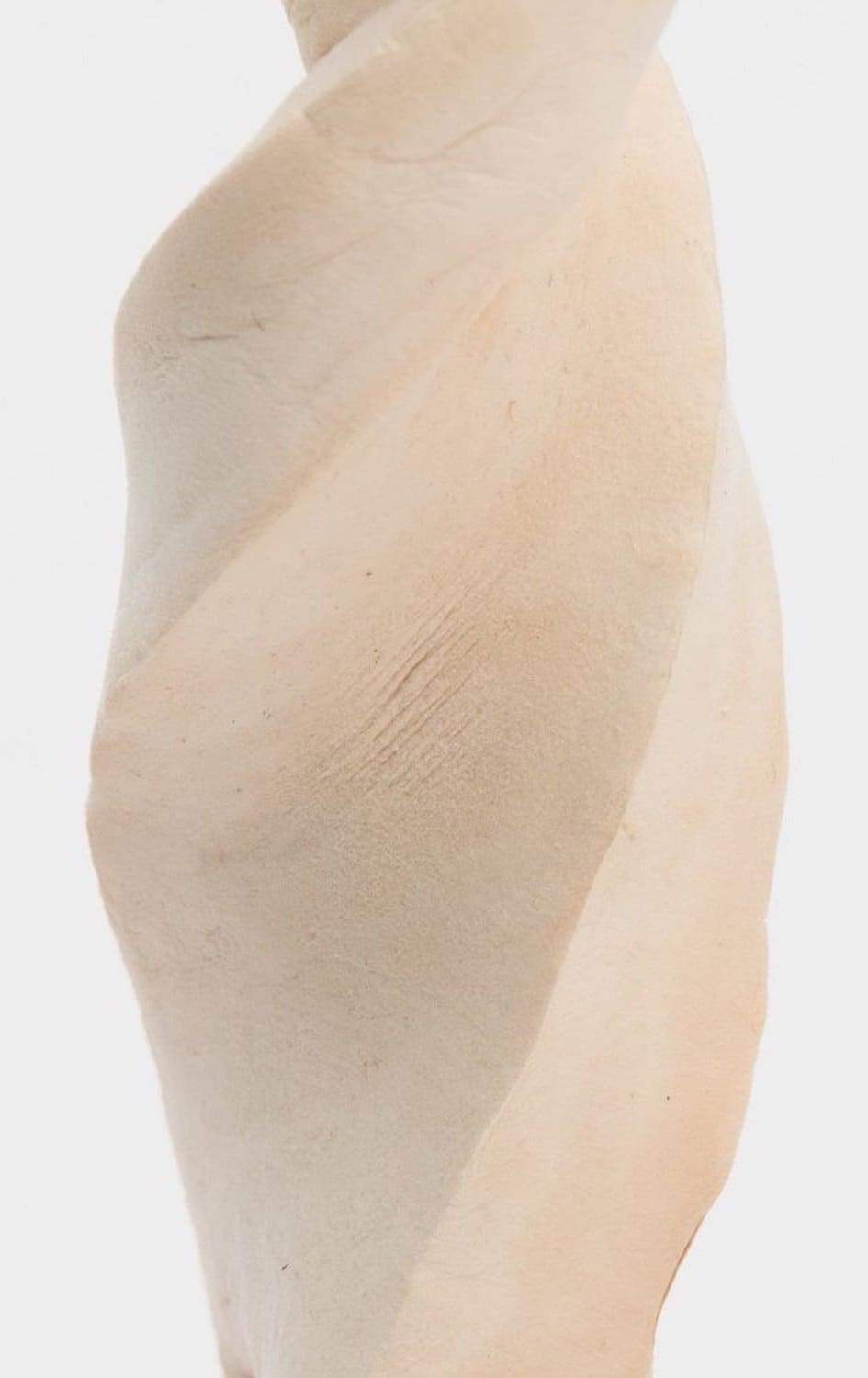

Our belief is that impact comes from the broadest possible adoption so we offer training and resources for others as well as developing our own products. Our latest products use our MycoFlex platform, which is a next-generation way of growing pure mycelium. This enables our vegan leather-like textiles as well as whole cuts of plant-based meat. They are different than any other mycelium product you will see, and we are just starting to scale and license that process.

You grow the mycelium at your foundry. Can you tell us about the process?

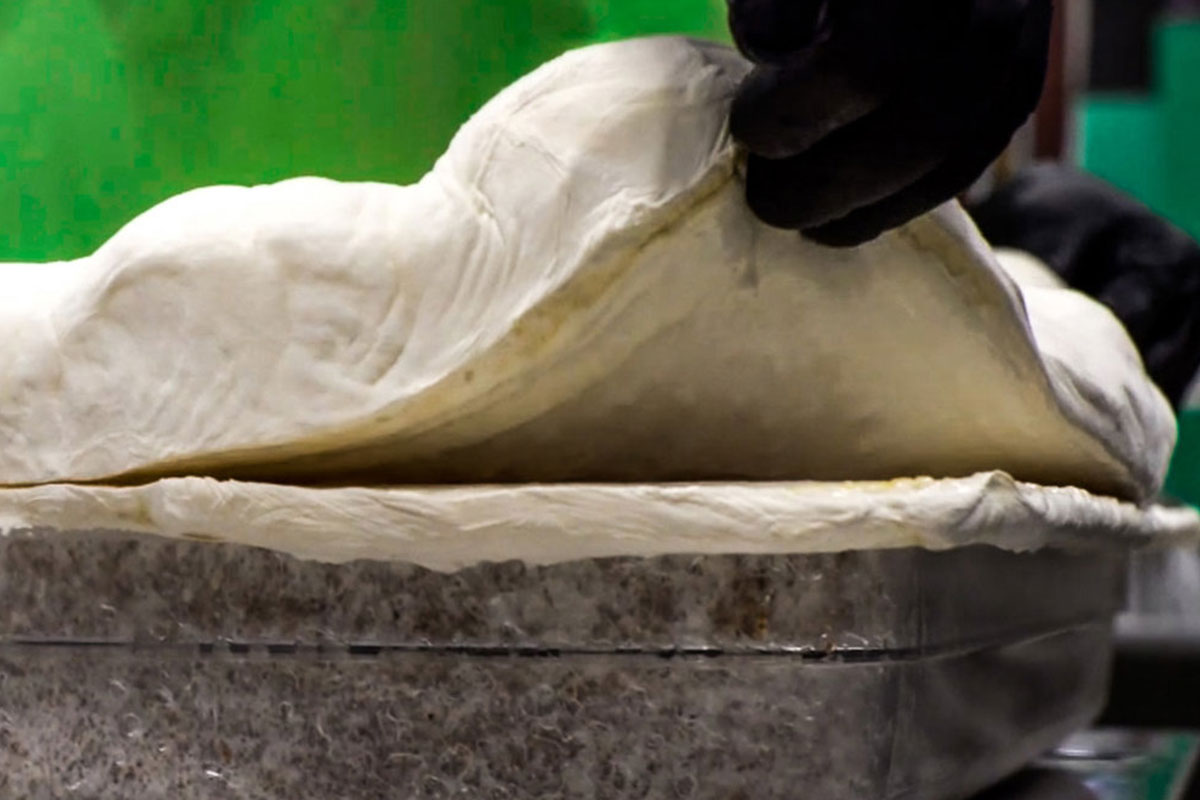

Most folks in biotechnology working with mycelium grow on liquid media and then destroy their cells at the end. The cells exist only to create an output, like beer in the case of yeast. In our process, we let the cells form beautiful and intricate 3D networks of mycelium that become the material, object or product. This means that we grow objects whole cloth—a piece of packaging, a chair, a whole building! This is entirely different than every other bioprocess today and we think it will be the future of biobased materials.

At Ecovative, our team has years of experience controlling the environment mycelium is grown in and which mediums produce specific qualities. Our groundbreaking research in mycelium has produced over 5 million pounds of Mushroom Packaging in the past few years. That is just a drop in the bucket compared to the amount of styrofoam produced each year, but we gain more ground on reducing plastics toxicity on our planet every day.

Currently, we are licensing our Mushroom Packaging technology around the world to help reduce styrofoam pollution; that frees up our talented team to continue new mycelium developments in textiles and our current focus, BACON! Imagine growing millions of pounds of Atlast® bacon in less than two weeks with a fraction of the water and land required to raise its pork counterpart.

You have said that the holy grail in meat is structure. What do you mean by this? And what role can mycelium play?

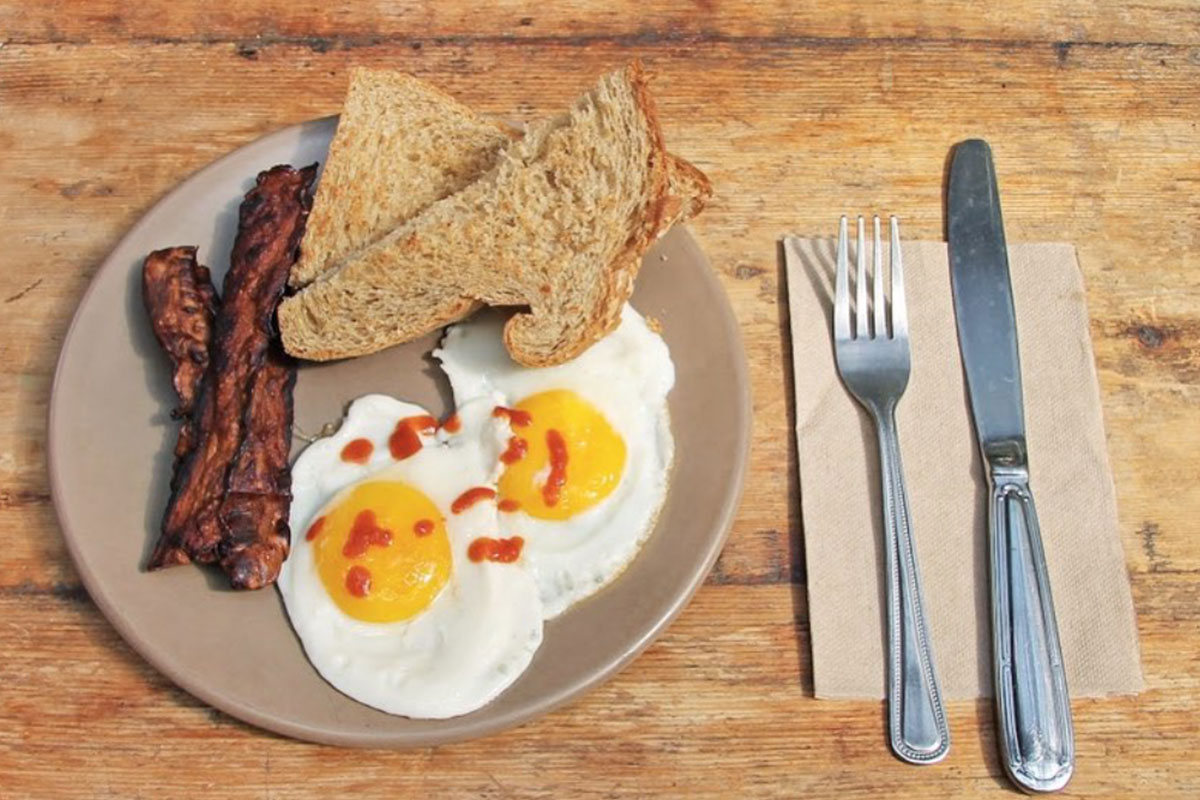

In the grocery store today we see all these ground and extruded meat alternatives on the shelves, but what about bacon, fish fillets, chicken breasts—no one is doing that, no has been able to do that, but we discovered we can make bacon, fish and chicken with mycelium. If you look at the market share in the meat industry, over 80% of meat purchased annually is a whole cut of meat, not a hamburger or sausage link; to really change consumers’ behaviors and have a significant impact on the planet, we need to provide them with what they crave and serve to their families—not just ground meat alternatives.

How difficult is it to create the taste and texture of meat with mycelium?

Now that we have the process down, it’s not that difficult, but if you asked me a year ago the answer would be different. We had a lot of trial and error before we found a viable product to bring to market that was a direct competitor with bacon. Have we found that perfect combination to make a grown piece of pig-free bacon? Yes, and it’s delicious. I even served it to my family at Thanksgiving this year and there wasn’t a piece left on the table.

This is possible because nature gives us a blueprint. Go out into the woods and you can forage for mushrooms that have a pork-like flavor and texture—they are hard to grow (sometimes taking years), rare, and typically take on the shape of a mushroom. We use these same strains but express the mycelium in days, not years, and rather than a mushroom, grow them into whatever shape we need, like bacon.

In regards to taste, mycelium can be grown to have specific textures and flavors. We have been growing, frying and eating bacon that tastes like bacon; chicken breast with a super juicy bite; and even substituting a specific gourmet mushroom species grown to mimic oysters or ahi tuna. We have also been hosting invitation-only Feast of the Future events for food industry professionals, and are collecting honest feedback and listening to people that have been in the meat or ingredient industry a long time to make sure we are getting it right. Gathering their insights has really helped us hone in on the perfect bacon that we hope to launch in the next year.

Which in-the-works mycelium products are you most excited about?

Atlast Food Co (Ecovative’s spin-off company). Creating Atlast Bacon and other whole cuts of meat is where I am putting my energy and focus in 2020. I think we can have a tremendously positive impact on our world’s food supply chain while also delighting meat-eaters. It’s poised to grow to a billion USD business over the next 5 years, so worth the attention.

My second passion is supporting the development of Mycelium Foundry One, our high throughput research facility which will be the best-in-class aerial mycelium research site in the world.

Are there any downsides to mycelium?

Mycelium is a natural material that eventually breaks down and returns to the earth like wood and bones. If you need a super long-lasting material that will be in direct contact with the environment—for a building foundation or a radioactive containment vessel—it might not be a good fit (though there are reports of radiation-eating fungi).

You are pro-GMO. Why?

I am very much pro-GMO and am very open about my stance on GMO’s. The ability to control biology, in higher-level organisms, especially like the ones we’re working with, will change the world in ways as significant as the personal computer. We have limited technical options to help the soon-to-be 10B people on Spaceship Earth without totally over-stressing and destroying our planet. Furthermore, we have an overwhelming urgency and obligation to help those most in need without clean water or access to medicine. Biology, specifically engineered biology, can help on both counts. Giving us the same materials and foods at a fraction of the environmental damage, and democratizing access to technology. Imagine sharing a sourdough starter with a friend that makes Aspirin or insulin—this would completely change the world.

Unfortunately, the way GMO’s were introduced to the world was not positive. If we were using GMO’s to add nutritional value instead of breeding pesticide-resistant foods, the public sentiment might be different. I think biotechnology is leading us down that path; it just might be a few more years until we get there.

At Ecovative, we work with native strains of mycelium that just work. We do not genetically modify any of the strains that go into our food products as there is no need to. They naturally create what we are coaxing out of them with the right parameters.

But other examples (like the sourdough starter that makes insulin) absolutely require it. Barring a massive change in our worldwide political system, leveraging biology is the only way I see to help the largest amount of people while preserving our home. Now would I love to experiment with genetically modified mycelium? Of course! But we don’t have the need for it at this time.

Can you talk about the notion of self-assembly?

Creating the next generation of high-performance materials—from leather-like textiles to performance plastics to plant-based steaks—requires a second step. Not only must we coax biology to create precise small molecules, but we must assemble those molecules in 3D space, growing fully-formed objects in a single step. Within the field of synthetic biology this idea feels radical. One day we imagine growing a home from a single seed, but how will we get there? Current approaches to engineered biology are aimed squarely at the molecular level, creating the building blocks used in industrial ecosystems from food to medicine to chemicals.

This is a noble and critical pursuit, but it stops just short of the fundamental promise of biological materials (the materials that make up the mighty redwood, the ivory in your old piano, and the biological machines called organs that animate the human body). The biological marvels combine two steps: molecular synthesis and molecular assembly, the art of moving tiny units around like legos to create fully-formed objects.

Can you imagine a future where we’re not dependent on petroleum-based products?

As a society, we have to imagine a future without petroleum-based products. Petroleum is a finite resource and as we exhaust the easy supplies, the environmental damage to get to the next tier keeps rising. More importantly, the materials we make with plastic never really go away. They bio-accumulate in the fish in the ocean and eventually in our bodies. There is a place for plastics and other petro-products in the world. It should just be limited to domains where that makes sense—definitely not disposable products! We have to keep looking at what has always been right in front of us and start thinking about it in a new and novel way to use our resources. That’s where the magic happens.